A while back I wrote a post about the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (SEP) that I described as ‘digital doxography’. While the alliteration was satisfying, the post was not, for the simple reason that it didn’t include any actual doxography. I’ve decided to make amends for this by using some statistical tools to see if the articles in the SEP cluster into any clear categories that we can regard as distinct philosophical schools. Specifically, I did k-means clustering on TF-IDF representations of the all the articles in the SEP published as of this week.

Document vectorisation: The idea is quite straightforward. Take a document. For each word in the document, count how many times it occurs. For lots of words, this will be 0, but for words like ‘the’, the frequency will be much greater (normally around 7% of the overall words). We then represent the document as a list of these numbers (i.e. a vector)and can do things like compare how similar one vector is to another using metrics like cosine similarity.

TF-IDF: There are two things we can do to make this process more informative. The first is to remove very common function words like ‘the’, ‘a’, and ‘of’ from consideration. These are called stop words and they don’t tell us much about the particular content of the article. The second is to weight the word frequencies for a document by how common the word is across all documents. A word that occurs a small number of times within a document might nevertheless be highly informative about that document because it occurs rarely, if at all, in other documents. The method we use for this is called TF-IDF (term frequency, inverse document frequency). It was developed in the early 70s by one of the founding mother’s of computational linguistics, Karen Spärck Jones. Spärck Jones worked at the influential Cambridge Language Research Unit (CLRU) alongside its founder Margaret Masterman who also compiled Wittgenstein’s Blue Book. For an interesting discussion on the influence of Wittgenstein on early computational linguistics, check out this great article by Lydia H. Liu.

K-means clustering: I capped the vector size at 10,000 dimensions. Although each dimension is itself interpretable (each dimension stands for a word), it can still be tricky to interpret this data en masse. To help with this, we can use k-means clustering to group the vectors into distinct clusters. This should, in theory*, group the documents into different clusters based on their content. The method for the is called k-means clustering.

In this case, I will focus exclusively on named philosophers, that is, philosophers who have articles dedicated to them, and cluster these into ‘philosophical schools’. I was very strict about this method – one article per philosopher, it doesn’t matter than Kant and Al-Farabi have additional articles for their logic, epistemology, aesthetics and so on. You don’t get extra points for being a nerd. After cleaning up doubles, that left 454 pages about individual philosophers, from Abelard to Zhuangzi, from Du Bois to Du Bos (yes, Du Bos was a real person).

There are two arbitrary features to all of this. The first is that k-means clustering starts with a random seed so I had to run it a few times to make sure that it was roughly producing the same results each time. The second is that I had to pick the number of clusters. This is a fraught issue. As Qin Shi Huang famously opined ‘100 Schools of Thought is too damn many!’, however, if you make your k too small, you can miss interesting clusters. Again, I used trial and error, ultimately settling on k = 20.

Now for the results:

I’ve decided to present the results in a fairly provocative way; I have come up with thematic headings for each cluster. These headings are based on vibes and should not be taken as a definitive account of the fundamental fields of philosophy. Along with thematic labels, I have included example figures, keywords associated with each cluster and anomalies to the thematic analysis. These anomalies were again based on vibes. I understand why Nelson Goodman would be included within Buddhist philosophy (I actually think this is a good analysis) but I have still marked him as an anomaly relative to the thematic label I proposed. I have included all of the data here and would love to hear your interpretation if you have a different one. I don’t know enough about ancient European philosophy to understand the different between clusters 9 and 10.

| Cluster | Theme | Figures | Keywords | Anomalies |

| Cluster 1 | Religious Metaphysics | Abelard, Leibniz, Origen | Divine, Soul, God | Margaret-Cavendish |

| Cluster 2 | Scepticism/Stoicism | Aurelius, Carneades, Sextus | Skepticism, Impressions, Stoics | |

| Cluster 3 | Modern Logic | Gödel, Barcan Marcus, Turing | Rightarrow, Logic, Carnap | William of Sherwood |

| Cluster 4 | Buddhism | Nagarjuna, Tsongkhapa, | Emptiness, Conventional, Dharma | Goodman, Kumārila |

| Cluster 5* (megacluster containing 1/3 of articles) | Metaphysics/Epistemology | Hegel, Du Bois, Wang Yangming | Reality, Experience, Knowledge | |

| Cluster 6 | Medieval Logic | Wyclif, Penbygull, Burley | Universalibus, Individuals, Signified | |

| Cluster 7 | British-Irish Moral Philosophy | Hutcheson, Murdoch* (Irish), Shaftsbury | Qualities, Morality, Human | Holbach |

| Cluster 8 | Medieval Jewish Philosophy | Delmedigo, Falaquera, Ibn Ezra | Law, Torah, Divine | |

| Cluster 9 | Ancient Philosophy | Aristotle, Olympiodorus, Philoponus | Commentaries, Pagan, Christian | Joane Petrizi |

| Cluster 10 | Ancient Philosophy | Zeno of Elea, Epicurus, Plato | Atoms, Plato, Zeno | Copernicus |

| Cluster 11 | Medieval Philosophy | Ockham, Peter of Spain, Erfurt | Motion, God, Sentences | Davidson, Reid |

| Cluster 12 | English Moral Thought | Anscombe, Hare, Sidgewick | Duty, Morality, Utilitarianism | Ayer |

| Cluster 13 | Religion | Anselm, Scottus-Eriugena, Meister-Eckhart | Sin, Divine, Things | |

| Cluster 14 | Islamic Philosophy | Al-Ghazali, Ibn-Gabirol, Al-Kindi | Existence, Soul, Intellect | Albalag |

| Cluster 15 | Political Philosophy | Marx, Fanon, Arendt | Citizens, Social, Government | Ayn Rand |

| Cluster 16 | Austro-Polish Philosophy | Twardowski, Meinong, Ehrenfels | Judgment, Gestalt, Content | |

| Cluster 17 | German Romanticism | Herder, Novalis, Schleiermacher | Bildung, Hermeneutics, Sculpture | |

| Cluster 18 | Confucianism | Confucius, Mencuis, Zhu Xi | Benevolence, Gentleman, Qi | |

| Cluster 19 | Multi-valued Logic | Weyl, Brouwer, Pierce | Intuitionistic, Geometry, Continuum | |

| Cluster 20 | French Philosophy | Du Chatelet, Descarte, De Grouchy | Mind, Body, Women | Hobbes |

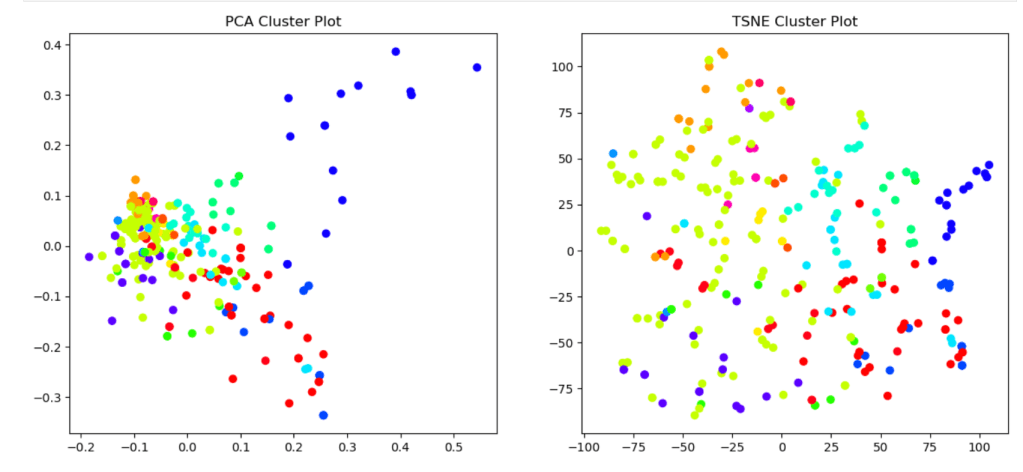

One nice thing about k-means clustering is that, once you have found your clusters, you can use dimensionality reduction methods like Principle Component Analysis or t–SNE to see your clusters beautifully spread out in a significant latent space. Well, I’m afraid this turned out pretty disappointing (I can’t even remember what the colours were).

Issues

If I were to do this again, I think the next step would be to include names among the stopwords. This is something I was ambivalent about. In part, philosophy is a dialogue across generations and so we can learn about a philosopher from who they were responding to or engaging with. But there is also some reason to ignore all this and just focus on what people were saying. I don’t want to debate the nature of philosophy but I do think that including names in the dataset can increase noise. For example, when k = 40, we find small clusters composed of the brothers Humboldt, and people called ‘Alexander’. When I ran the k-means clustering with k=2 in order to discover if the two fundamental kinds of philosopher comprised distinct clusters, it seemed to suggest that philosophers do indeed, at the deepest level, fall into two groups. They are either called William or not called William. The second obvious step would be to import a constraint on the possible size of clusters. The current analysis is dominated by two very large clusters (one contained around 1/5th of the dataset), which obviously isn’t desirable. I suspect the k-means constrained package should be able to help here.

* ‘In theory’ isn’t the right way to put this since it’s not clear what the theory is. Maybe we need a new term for engineering decisions using stochastic methods like this; ‘in algorithm’.